When it comes to art cinema, and slow cinema, I often think of an ideal viewer that must exist who is 100% alert and awake, and intellectually keyed into the symbolism and poetics that might take place. But then again, why should I judge myself against an ideal viewer that doesn’t exist? If you fall asleep, you fall asleep. Rewind and re-watch. If something goes over my head, I can just zero into what makes me think, or feel. Or even just appreciate the aesthetics, and the intention. That something like this strange art film exists.

Late at night and I couldn’t sleep, lying in bed listening to music, before I decided to decamp into the living room and start watching something. When I selected the Marguerite Duras film to watch, Le Navrie Night (1979), from the Rarefilmm website, I was hoping it would fit the circumstances. And in the first five minutes, I knew it would. The opening narration talks about the stillness in a night, the silence, and the proceeding film feels like it lives in that stillness, despite how talky it is. Cameras pan across empty spaces and the story is about two lovers who only communicate over the phone during the night. It was an ideal circumstance to watch, sleepless in the morning hours and existing in the film’s poetic reverie.

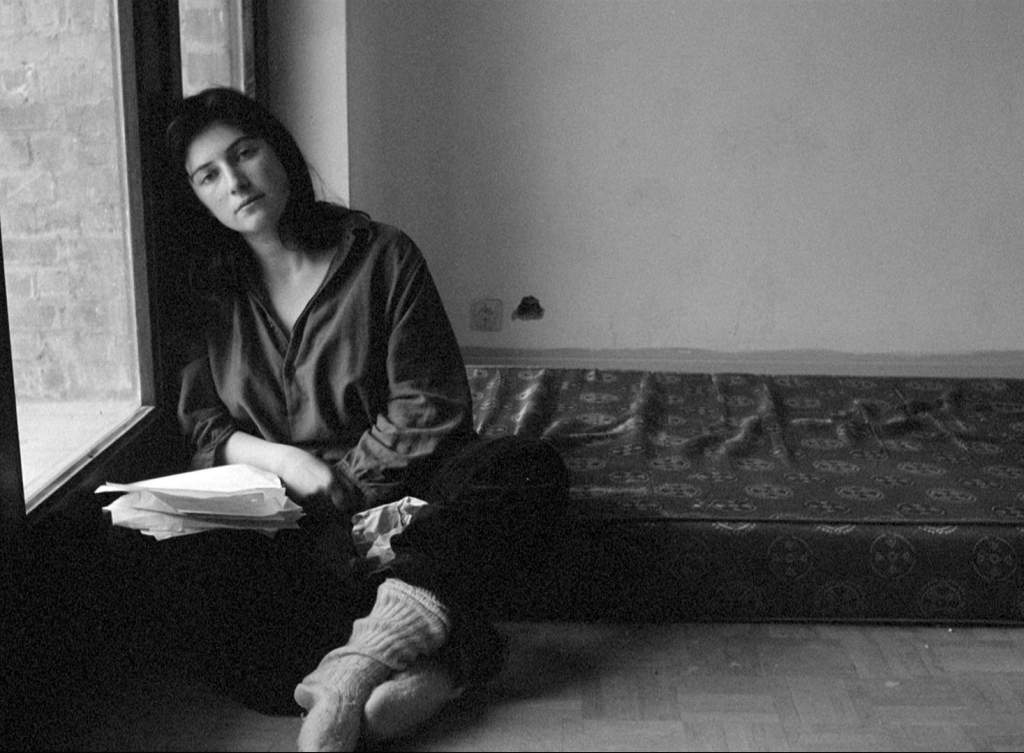

Duras is an author and her approach as a filmmaker seems to prioritise the power of words, taking a postmodern approach to the medium. There are a lot of distancing effects. The story is told mainly by voice-over with Duras telling the narrative, not from a first person perspective but describing the characters in third person. A country estate is the location of the film shoot, and we see the film lights in the corner of the room. Three actors are assembled (Bulle Ogier, Mathieu Carriere, and Domnique Sanda). They ask questions to the off-camera director of the stories being told, and one by one we see them getting make-up applied in close-up as they sit in silence. But they don’t play the roles written. They are mainly visual points of interest in the frame as the story is told over the narration. Sitting, or standing, as the camera pans around the house’s interior. Though a writer by trade, Duras and her collaborators also create great film images. There’s a slow shot of a camera panning down the seine river at dusk which I thought was especially beautiful.

The story? Two people fall in love over the phone, and their relationship is only carried out through late night telephone calls. There are complications involving sickness and class, and the effect is hypnotic. It is slow cinema and I did have to pause the film and fall asleep on a couch before resuming. The micro-nap was satisfying and when I woke up, I returned to Le Navire Night and continued watching. I didn’t necessarily feel a strong connection to the story of the lovers, their trials and tribulations, the confusions and the doublings of identities. I was more taken in by the way the story was told, the empty spaces outside, or in the outskirts of Paris, the slowly panning camera as the voices talk over the images. Or the actors standing in the frame. Or the wooden table lit gloriously within the darkened living room. Duras and her crew create an overall mood and an atmosphere of haunting loneliness, and the hook of a spoken word, even if it’s faceless and transmitted across time and space. Recommended.