The copy of director Lucio Fulci’s Don’t Torture A Duckling (1972) on Tubi that I watched felt like it was an older DVD transfer uploaded as the image quality was desaturated and a little fuzzy, which added to how the Italian village of Accendura comes across in the movie. The rocky hills seem almost yellow and the town centre, which is made of white stone, feels further visually drained of life.

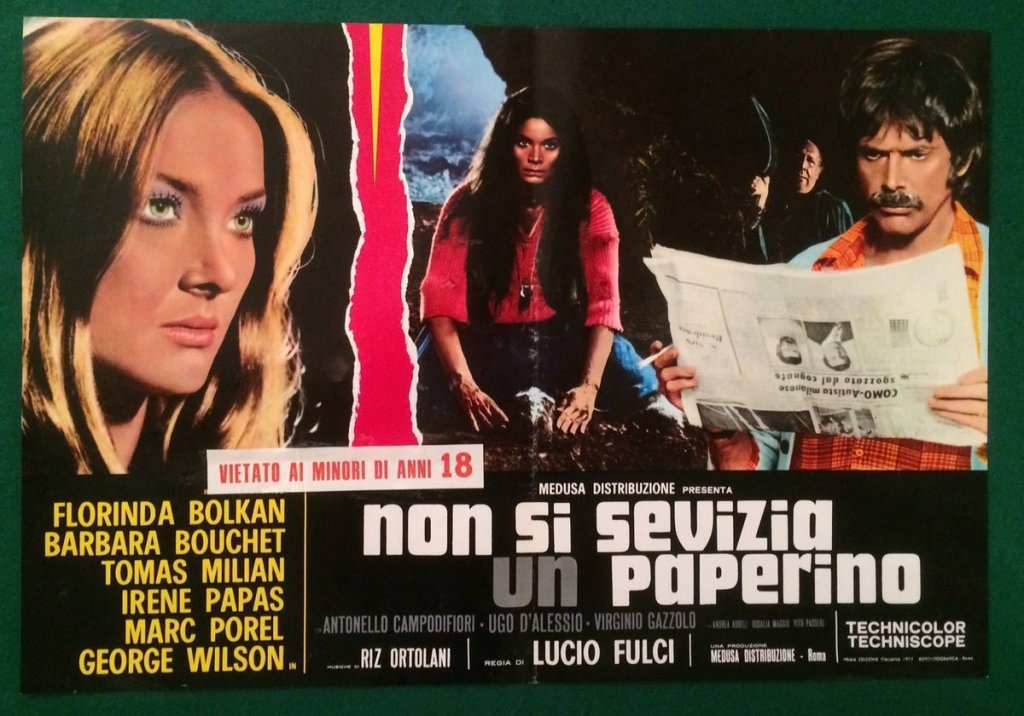

Aside from the presence of sex symbol Barbara Bouchet (from The Red Queen Kills Seven Times) – playing the daughter of an absent rich industrialist, moved back to her hometown to kick her drug addiction – this giallo thriller feels different to the others shot in Rome, or taking place within the fashion or publishing industry. There’s not a lot of glamour in this provincial existence and that’s further compounded by the string of child murders that upset the town’s quiet existence, and add an eerie atmosphere to the film’s thriller mechanisms. As young boys turn up strangled and bashed, the police and an outside investigator pursue leads and a few suspects, each one causing the town’s mob mentality to rise up. Even as a newspaper man (Tomas Milan) and Bouchet’s character eventually become the film’s main investigators, there doesn’t feel like a fixed protagonist and everyone feels included within its procedural narrative. One of the most striking characters is Florinda Balkan (from Fulci’s A Lizard In A Woman’s Skin), harried and unkempt, observed in the opening scenes digging frantically in the dirt upon a hill and finding the bones of a baby’s skeleton. We find out later that she is an outcast who believes in witchery and black magic, and there are hidden secrets among the townspeople, as well as a latent capacity for violence.

Don’t Torture A Duckling has that narcoleptic quality, which I do enjoy, of giallo thrillers; usually I find giallos a bit sleep-inducing due to the drawn-out, convoluted mysteries, and yet here there’s a clarity to what’s happening even as the identity of the killer is held back until the very end. For the majority of its length, I thought this was good, a solid thriller, and was wondering a bit why it’s held in high regard for Fulci fans. Apparently this is one of his first films to get stuck into gore and body horror, and there’s a clear and striking sequence halfway through where Fulci’s brutality is on display, a very upsetting moment that underscores his critique of small town mentality. And then I was like, oh I get it, this is a strong Fulci moment! The other clear highlight is the very ending, more because of its absurdity as it collapses tones between an image of gore-laden violence and sentimental music by Riz Ortolani, a strong conclusion that speaks to the specific quality Fucli has as a horror filmmaker that would be expanded upon in his later masterpieces like City Of The Living Dead.

Even if a body looks like a fake dummy, as long as it can be demolished to show skull and blood, that’s cinema, Fulci-style! Recommended.