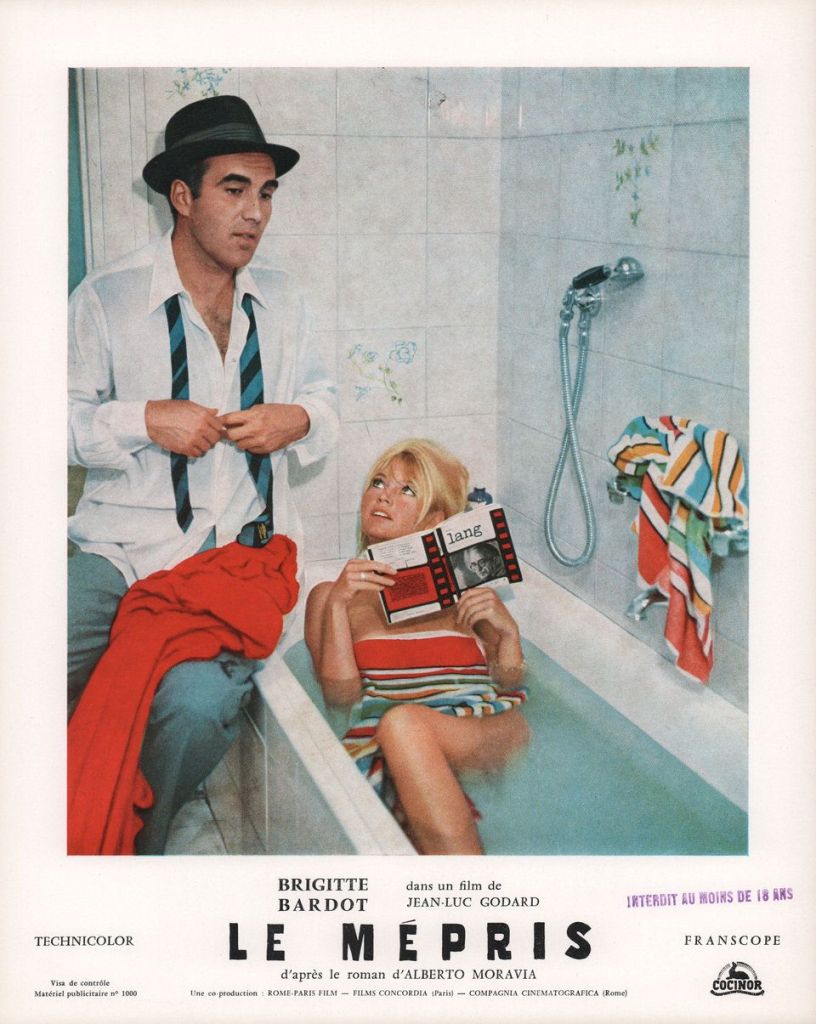

Contempt (1963; Le Mepris) was a film that I admired or appreciated rather than loved. I’ve long read about it, seen it discussed by film critics and directors, and it did help to learn this was director Jean-Luc Godard’s only film financially backed by American film producers and that he didn’t like the filming experience. And that the producers wanted more scenes of star Brigette Bardot in the nude to help sell it financially on the back of her global status as a sex symbol. There’s a meta-textual aspect to the story as it follows French writer Paul (Michel Piccoli) who is asked to help write new scenes by an American producer Jeremy Prokosch (Jack Palance) for an adaptation of The Odyssey for director Fritz Lang (playing himself). However, the producer also seems very interested in Paul’s wife, Camille (Bardot), and despite the married couple’s intimate moment together in the opening scene, there is a growing distance between them, compounded when Paul sends Camille off with Prokosch and turns up late at the producer’s villa. Is Paul engineering an affair to get out of his relationship? Is this a metaphor for selling artistic integrity? Is this an expression of Godard the director’s own separation from then wife Anna Karina? The protracted argument between Paul and Camille in their apartment has been widely celebrated, and it does feel more real in its on-going back and forth than maybe melodramatic arguments depicted in Hollywood movies at that time. For me, personally, I don’t know if I was invested in them as a couple and it felt more like an analytical exercise than something that was a tragedy, and I don’t know I got any emotional interiority from them despite the use of voice-over narration. The sense of emotion truly comes out of George Delerue’s magnificent theme (also used by Scorsese in Casino). I did delight in the performances of Piccoli, Bardot, Palance (especially adding a wry comic energy to his archetypal character) and Lang representing a closing chapter on film production and types of Hollywood movies being made at the time. I appreciated more the use of colours and framing, the occasional inclusion of fast camera moves or montage within its style, almost as if becoming more epic and stately than Godard’s earlier work in the New Wave. Maybe in time with revisiting, it might hit harder, but I was more fascinated by Contempt as a cinematic object than felt it as an emotional experience – then again, that might be Godard’s point.