“The one thing I can’t bear now is atmospheres. I can come into a room full of people and I can tell you who’s had the row. I always say: if I’ve upset you, just come out with it. If you cold-shoulder me, I instantly see him [my father] sitting in the corner of the parlour and I’m a seven-year-old again.”

I find Terence Davies very charming to read in interviews, or to watch being interviewed. To hear him talk about his upbringing, or to understand his connection to the past, and his preference for it. And yet, being from a working class background and arguing for the British Film Industry to move on from its mainstream preoccupations with the same actors or Jane Austen adaptations. That he was gay but mostly celibate, and could mostly pinpoint the period of his life when he was happiest (a four year period after his father dying and before he was bullied in high school). All of it helpful context to understanding his first film, Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988), a bit further. But even without that autobiographical knowledge, there’s the pull of mystery to the film. A recurring motif are family members grouped together posed for a photograph. A wedding, a funeral, another wedding. The post-war era of standing still, looking serious at the camera. To think of the changing culture and social tradition of family photographs, the growing permission to smile or look goofy in subsequent decades, or to not be locked into a stiff pose. Images of the past. And here they are, living memories recreated and captured on film.

The film’s wikipedia entry has specific details about the Liverpool locations where Distant Voices, Still Lives was shot. That the front of the family’s home is authentic to the older period, and yet there’s a theatrical quality. A presentational staginess. We flow from moment to moment, back and forth in time from the children to them as adults thinking back on their past, working within a larger reflection by the director. “Nostalgia is a poison” is a sentiment used again and again to fight back against “the good old days,” and the film’s rumination of working class British existence feels balanced. These traditions, the radio programs, and the cost of things, etc., documenting all the of which is now gone. Reviving it all, and seeing it clearly though. The violence of an abusive father, and the wider cultural codes of angry husbands and shackled lives. Balanced by the love and warmth of siblings, of the mother, of breaking out into song at every moment. Singing together in sadness, singing together in joy, singing together to remember, or to forget.

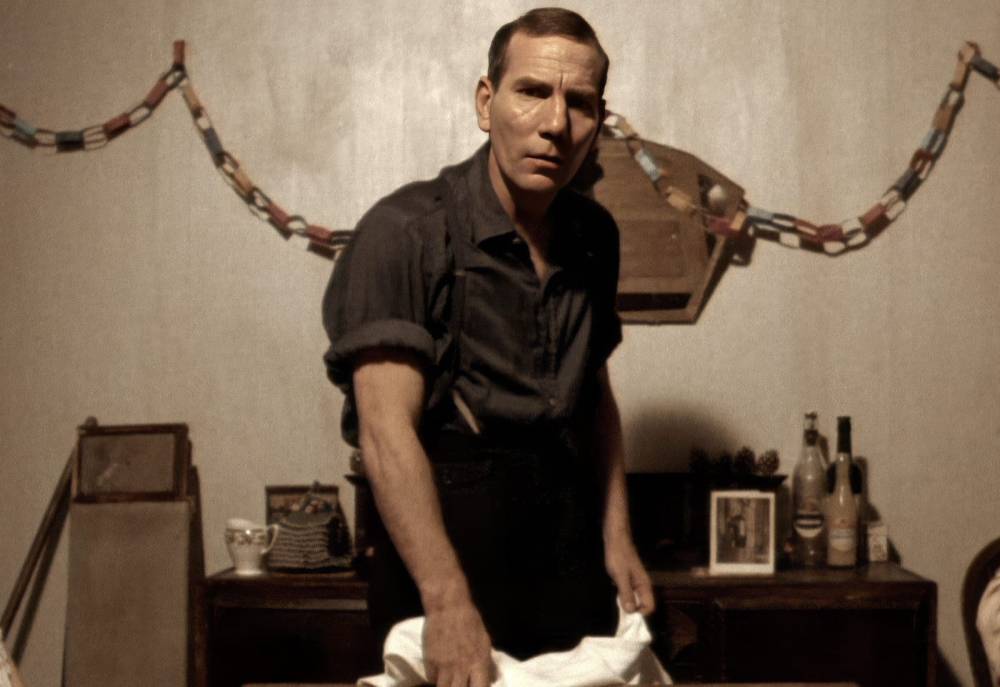

Pete Postlethwaite remains an intimidating presence onscreen, and even more so as “Father” whose capacity for rage and violence is conveyed effectively in the first part without having to linger or dwell. The “atmospheres,” as Davies terms them, is successfully established even when Father is gone. Freda Dowie is moving and memorable as “Mother,” how she carries on past as a stalwart presence for her children, even as they move on with their own marriages.

There were two points in Distant Voices, Still Lives that I had very strong emotional reactions to, and would think about its filmmaking days after watching. At this point I had only seen The House Of Mirth from Davies’ filmography, out of adolescent X-Files fandom over Gillian Anderson and seeing her in an Edith Wharton costume drama. But am keen to follow up with the rest of Davies’ work, and particularly his next film after this, The Long Day Closes.

Distant Voices, Still Lives available to stream on Kanopy. Recommended.